Are College Entrance Exams Good for Something?

The pendulum is starting to swing back on the test-optional trend, but education reformers should think about why.

For a few years it looked as though the ACT and SAT might be on their way out. Colleges across the country were dropping them as a requirement, and they enjoyed increased applications as a result. But then some schools started to wonder what had been lost when they stopped getting what used to be a central data point in their process. Now, Harvard and Cal Tech, convinced that the tests are a better indicator of potential, are bringing them back. K-12 schools follow this debate with some interest because of the effects it has on their students, but it has not inspired enough reflection on why SAT scores might contain more information than a transcript four years in the making.

The grand test-optional experiment which expanded to nearly 2000 colleges at its peak, took as fact that tests did not indicate much that was not already known from other indicators such as GPA. The most selective colleges, however, now argue that they know better now. The pendulum has swung back and colleges are finding that maybe they were wrong. One explanation for this reversal is that colleges have found the tests contain more information than initially thought. Another explanation is that, while tests are not perfect, they are better than GPAs, which contain very little information. I think there is a third explanation: high school transcripts need ACT scores to contextualize them. Together they make more sense than either of them alone.

Colleges are right to be skeptical of GPAs. Grades have always been subjective indicators of academic ability. The grading practices and rigor vary wildly from classroom to classroom even within the same school. We could easily blame grade inflation as the source of the inaccuracy in GPAs—if everyone has a 4.0, what unique information does it contain? But grade inflation as a trend started well before colleges started to drop their test requirements.

Already by 2016 there was a trend starting toward higher GPAs despite lower NAEP scores. The NAEP is a randomized, well-calibrated study of students’ ability, so the divergence seems to indicate something real about grade inflation. The fact that GPAs increased during and through the pandemic, a time when no one would claim higher academic achievement, further proves that an A does not mean what it used to.

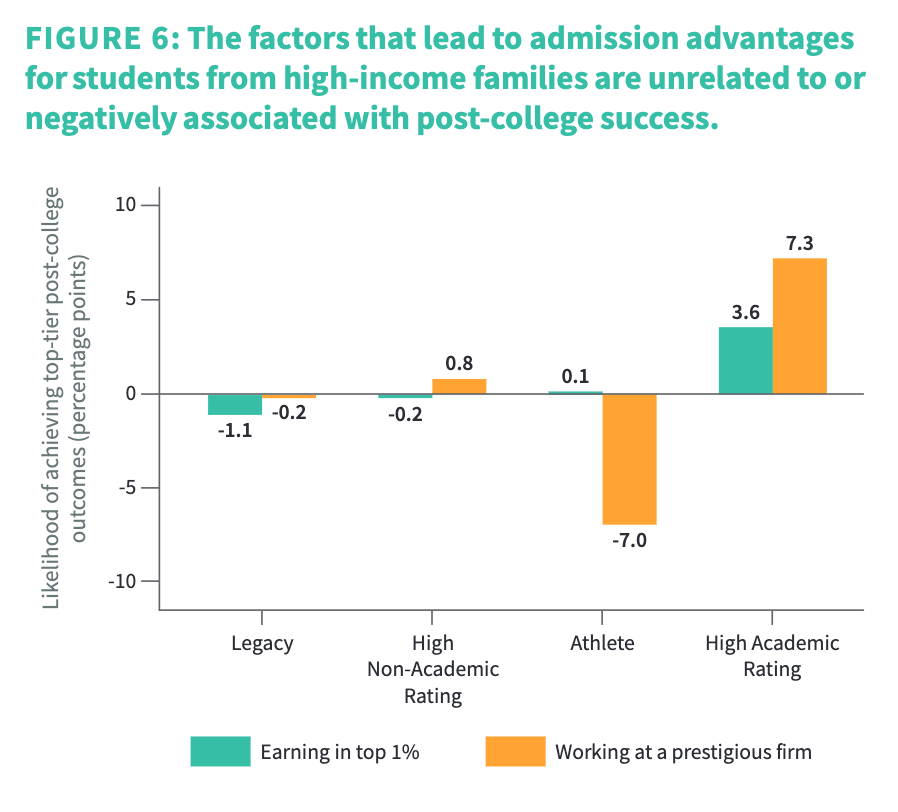

Why did colleges drop college entrance exams at exactly the time when they might be most important? Simultaneous to the upward trend in GPAs, the nation was searching for ways to create greater diversity and equity on college campuses. The theory was that not requiring an entrance exam might entice good students who have lower scores to apply and let their resumes speak for themselves. Except that doesn’t work. A study conducted by Opportunity Insights found that high income students—a group selective colleges have plenty of—were more highly rated on their non-academics than low income applicants. The SAT, it seems, might have been a way of actually balancing the biased scales of admission. When colleges lose the objective academic data, they are fall back on more subjective criteria that favors the wealthy.

It’s hard to believe that colleges didn’t already know this. After all, admissions departments review thousands of applications year after year. Many of them must have gathered enough data internally to know that SAT scores provide useful information. Admissions departments misjudged the importance of college entrance exams because they misjudged what grades represented.

Grade inflation is only one of the problems with high school grades. To be sure, GPAs have been creeping up, but a much harder problem for colleges to detect is that grades are divorced from actual content knowledge. If an A used to be a B, that’s grade inflation, but if neither the A nor the B ever represented the learning that should have happened, then inflation is irrelevant. While grade inflation may be a more recent phenomenon, courses have long been misaligned with their content. The standards-based movement of the last 30 years reveals the problem. Too many courses do not teach what they are supposed to teach, so even the highest grades do not indicate much about content knowledge.

College entrance exams, on the other hand, pretty reliably indicate something about ability. In fact, they are a much better indicator that students will have success (monetarily, at least) after college than non-academic factors. The evidence points to college entrance exams providing useful information. That is not to say that grades or resumes or letters of recommendations do not. Instead, I think that test scores give those other elements context.

Richard Elmore’s observation that the instructional core—teacher, content, and student—is all that matters, still applies, and I think colleges stumbled into realizing that the grades that come out of that triad are only as good as their core. They know now that the variability of that core across all the transcripts that come to the admissions office makes grades unintelligible. The decoder ring, the Rosetta Stone, are the college admissions tests. With an ACT score next to them, colleges can get some sense of whether a good GPA means something about a student’s knowledge or not. As much as people may hate them, they are a commonly understood standard that makes grades mean something.